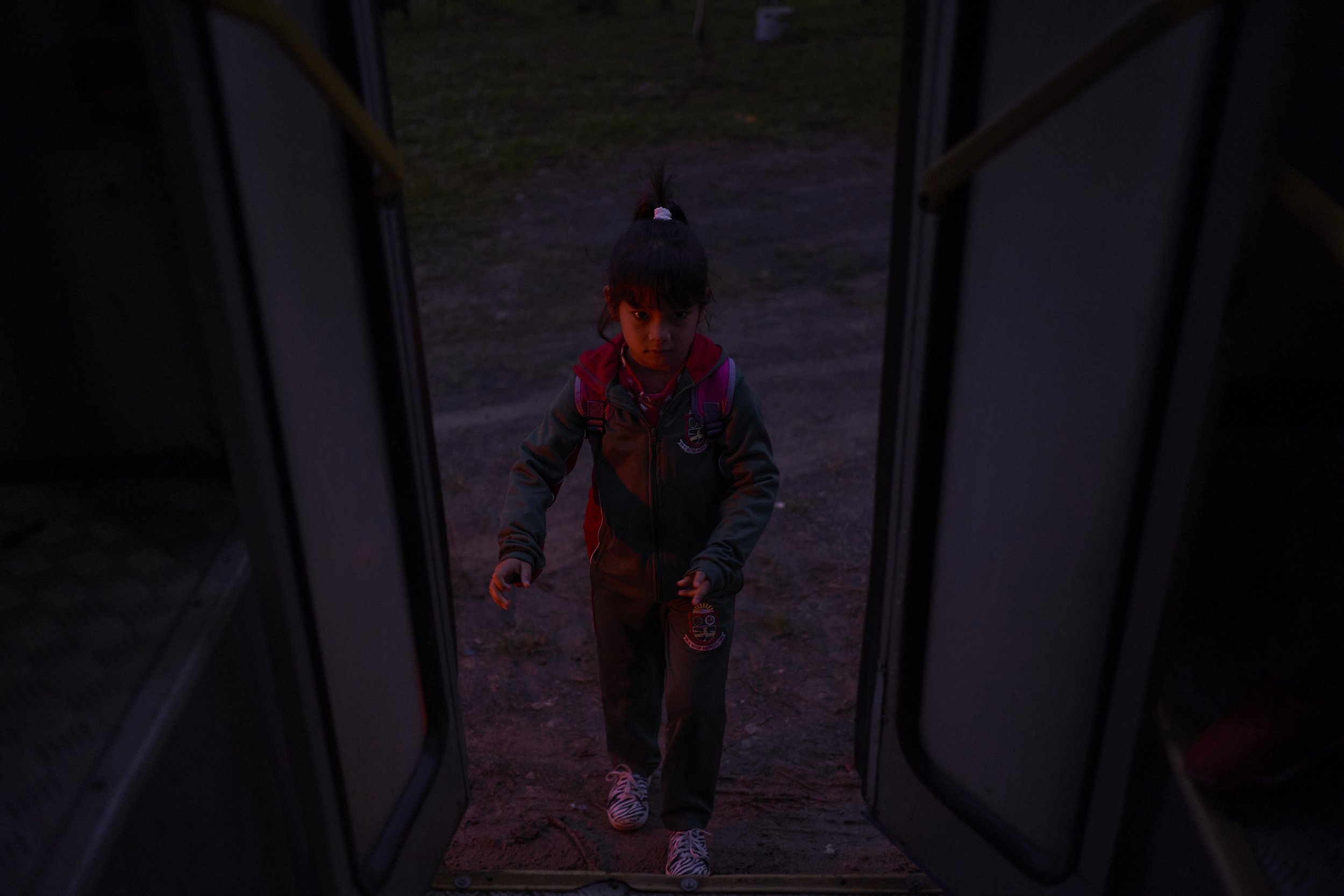

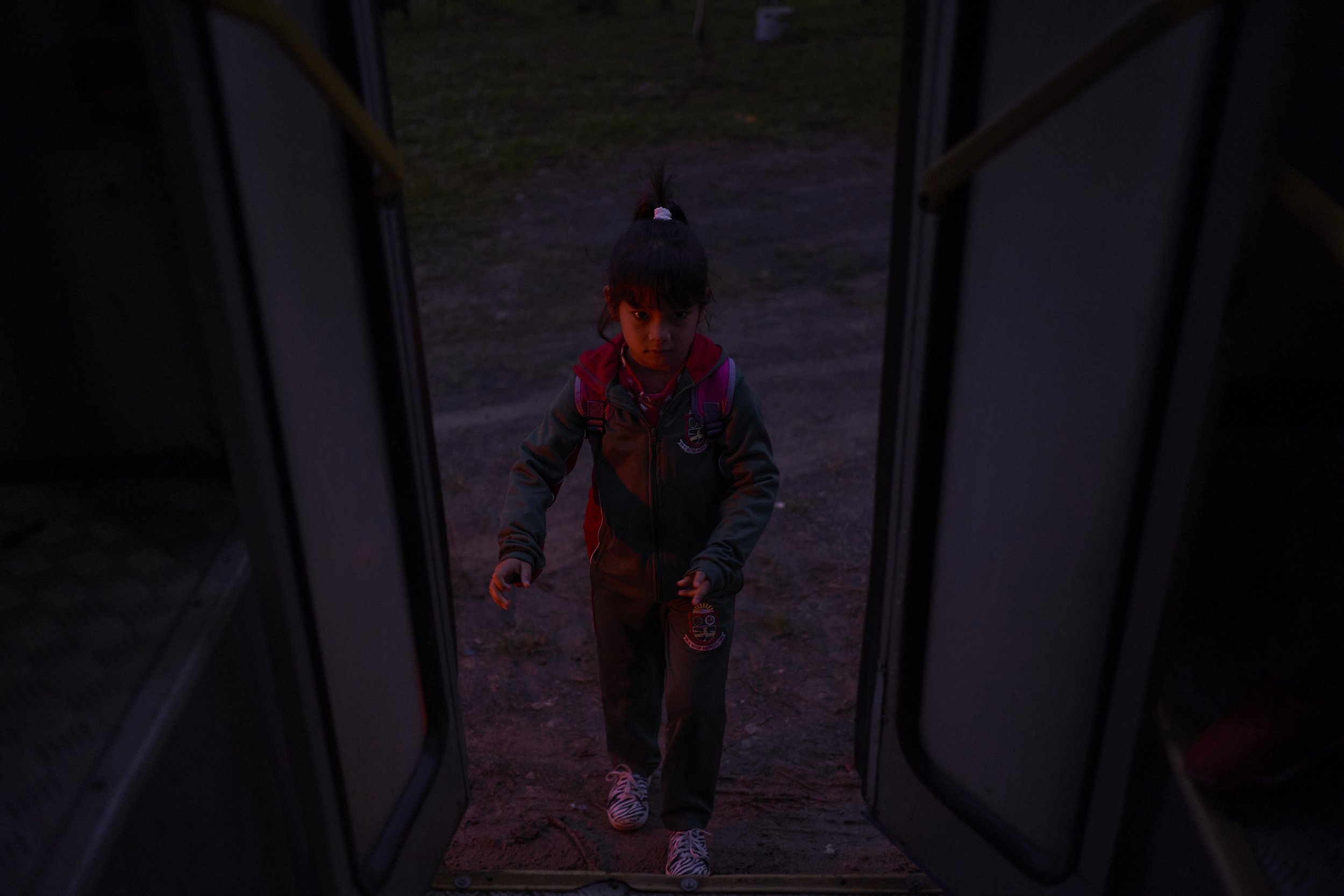

Tandara Katxa Maciel De Almeida walking home at the Ibirama-Laklãnõ Indigenous Territory. Indigenous Xokleng children lives continually fluctuate between feelings of fright and some degree of hope.

The decision of the “marco temporal”, a cut-off date limiting Indigenous land claims, a restriction sought by the powerful farm lobby to block rights to land that Indigenous people did not live on in 1988, is a legal policy supported by businesses and farmers seeking to use Indigenous land. They have the power to define not only the future of the Ibirama-Laklãnõ Indigenous Territory but the future of all Indigenous lands in Brazil.

Moreover, it will define the future of all children, including non-Indigenous children, because our ability to grapple with a mutating climate and its devastating impacts depends on the conservation of Indigenous territories.

Brazil is home to 1.6 million Indigenous people, according to its latest census, and ancestral lands form an essential part of their culture and livelihood.

Yara Carolina Conlam Lerlonda gets into the school bus. The bus gets her and other Xokleng kids at the Ibirama-Laklãnõ Indigenous Territory, and non indigenous kids outside the territory.

Xokleng families fear that “the white people who are debating the ‘marco temporal’ [historic cutoff point] will doom their children’s lives.”

Yara Carolina Conlam Lerlonda and Emanuele Victoria Pereira de Jesús on their way to school. The bus gets them and other Xokleng kids at the Ibirama-Laklãnõ Indigenous Territory and non indigenous kids outside the territory.

Teens reenact the genocidal violence that generations of their people store in their memories.

Organized by the students with the help of teaching staff, this is a reenactment of attacks by burgeiros, the mercenary killers of Indigenous people who were paid by colonizers, European immigrants, and the government. These open wounds were left by the encounter of Indigenous and white people during the colonization of southern Brazil, which intensified in the 1850s, and then by the confinement of these Indigenous people to an area of some 150 square miles , starting in 1914—the date the Xokleng Laklãnõ group agreed to establish friendly relations with the non-Indigenous, through the intermediation of Brazil’s former Indigenous agency, known as the Indian Protection Bureau. More than a century later, memory forms a bridge between hatred in the past and racism today.

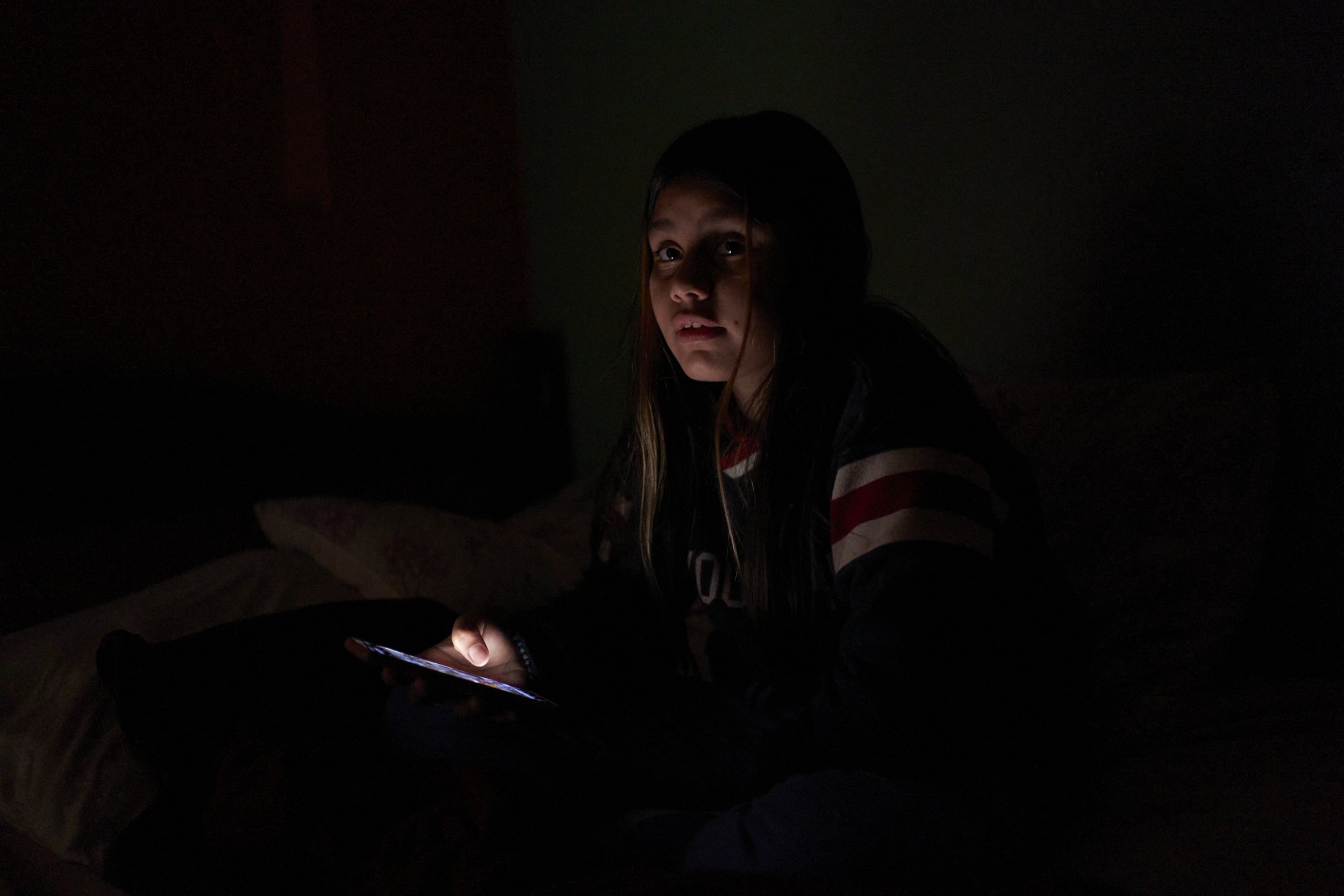

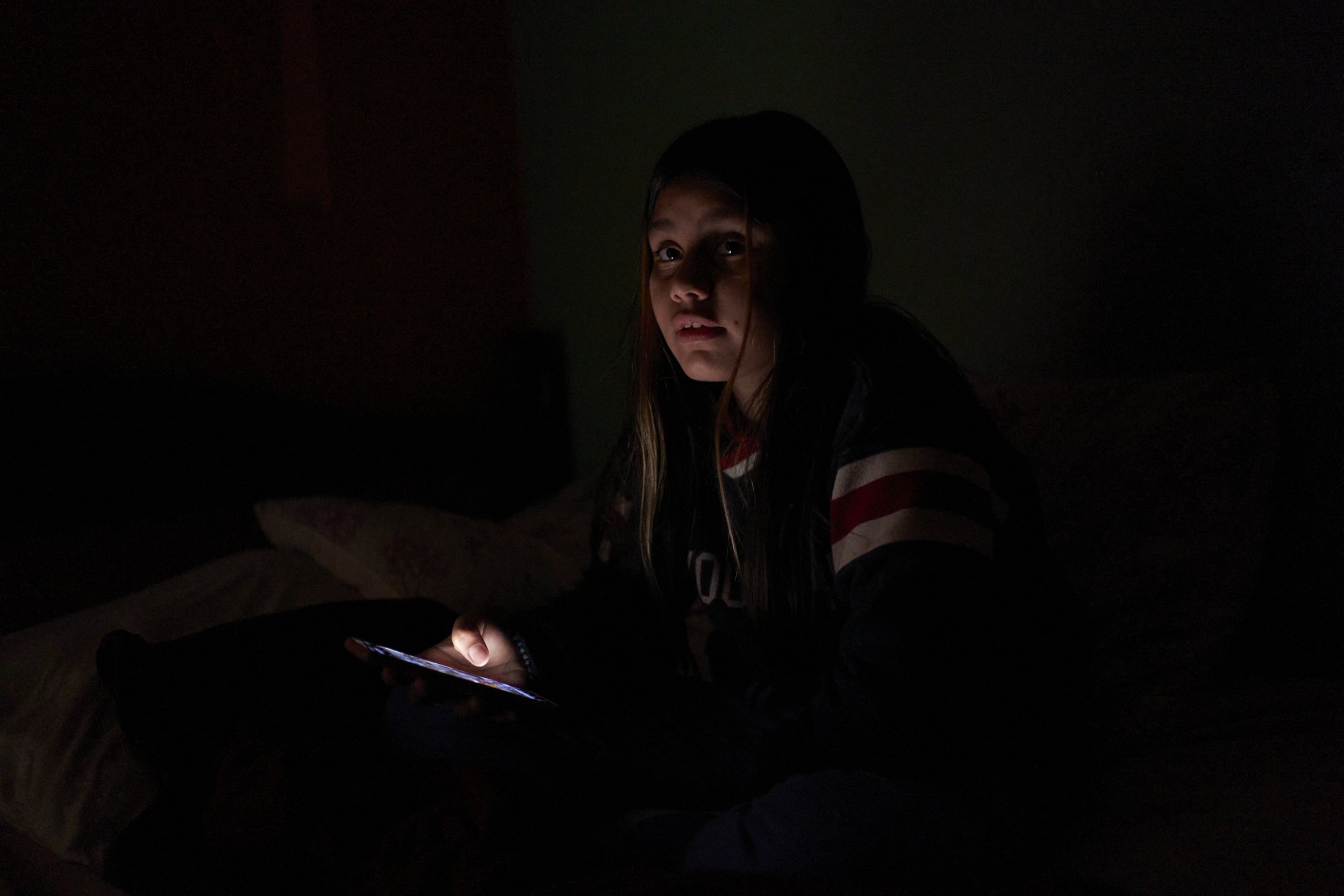

Hadyja Amedo makes a post on her instagram.

Hadyja, 10 years old, says she’s going to study law so she can defend the Xokleng people. On her Instagram page, which is monitored by her mother, the girl introduces herself as a ‘young Xokleng leader.’ In 2020, the Military Police threw pepper spray in her eyes during an Indigenous mobilization in Brasília, baptizing her to the struggle. “There were tears and distress, but we learned a lesson about what can happen when we take part in movements for our rights,” says Thaira, Hadyja’s mother.

Decoration in the Caxias Patte family home, in the Terra Indigena Ibirama-Laklãnõ Indigenous Territory.

Xokleng children Xandrei Batista Braga sleeps while coming home from school, in the school bus.

Jostling along a bumpy, winding road, they ride 15 miles every day school. Of the 45 students enrolled there, 35 are Indigenous. Even so, the principal prohibits any “political” discussions, like talk about the “Marco Temporal”.

Eduarda Wanhkyl Kágfej de Lima Tschucambang poses for a photograph in her home.

In April this year, Eduarda Wanhkyl Kágfej de Lima Tschucambang, 15, was at an agricultural show in Rio do Sul, a city in Itajaí Valley, representing her municipality of José Boiteux, when she heard someone say “Indians should evolve and leave their huts, just like white men left their caves.” Hurt by the white man who had recognized her Indigenous features—along with her earrings and a bracelet with ethnic graphics—Eduarda stopped handing out leaflets inviting people to a traditional party and decided to leave. Her mother, the Indigenous teacher Josiane Uglon, says it was ten at night when her daughter came back crying and went straight to her room.

Teens dance and sign Xokleng songs, reclaiming their land, at the indigenous High-school Laklanó, inside the Ibirama-Laklãnõ Indigenous Territory.

Teens dance and sign Xokleng songs, reclaiming their land, at the indigenous High-school Laklanó, inside the Ibirama-Laklãnõ Indigenous Territory.